February 25 – April 10, 2010

There is nothing natural about a natural history museum. ClampArt’s exhibition, “The Museum of Unnatural History,” illustrates this axiom through the display of photographs and paintings by Richard Barnes, Justine Cooper, Jason DeMarte, Blake Fitch, Jill Greenberg, Nicole Hatanaka, Harri Kallio, Hippolyte-Alexandre Michallon, Lori Nix, Matthew Pillsbury, Elliot Ross, Amy Stein, and Marisol Villanueva.

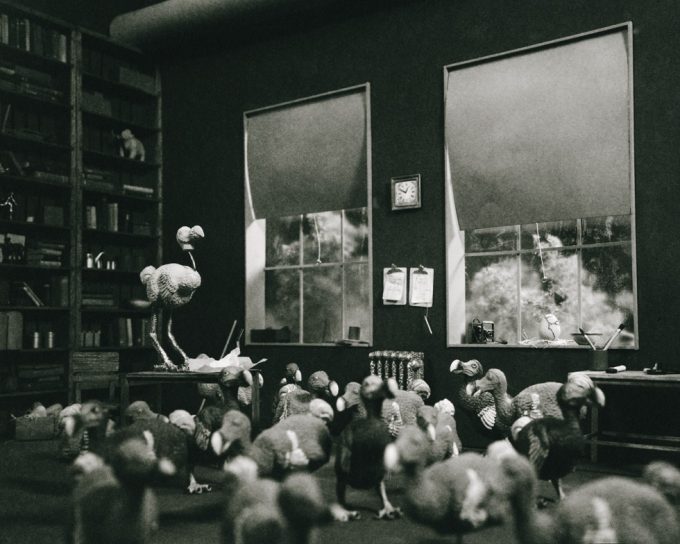

The theme for the show was originally inspired by Lori Nix’s new series, “Unnatural History,” in which the artist painstakingly constructs tiny dioramas of rooms in imaginary natural history museums and photographs them in black and white. The final platinum palladium prints are hilarious scenarios picturing madcap, behind-the-scene possibilities, which highlight the curious oddity of our historic need to amass, conserve, and display elements of the natural world. Nix’s photographs reference and bring to mind other contemporary artists inspired by the natural history museum and the often bizarre and awkward artifice inherent in the scientific presentation of the animal kingdom.

Many of the artists in “The Museum of Unnatural History” depict the museum directly, including Barnes, Cooper, Fitch, Hatanaka, and Pillsbury. Whether imaging the dioramas and displays found in the public areas of the museum or the storage facilities and offices off-limits to visitors, the artworks question what motivates us to collect—be it knowledge, ownership, or facile curiosity. Pillsbury’s photograph of the Grande Galerie de l’Evolution in Paris, for example, pictures a parade of giraffes, zebras, rhinoceros, and other African beasts presented as a spectacle of fauna. These animals are displayed and housed in an elaborate manmade structure—a structure dropped over the complexity of nature in a vain attempt at total comprehension and control.

Other artists such as DeMarte, Kallio, Villanueva, and Nix (mentioned above) take the museum and its displays as the inspiration and impetus for their imagery, mocking and morphing our obsession with the classification and collection of the natural world often through the lens of pseudo-scientific precision.

And finally, Greenberg, Michallon, Ross, and Stein represent animals through either tongue-in-cheek academic draftsmanship (highlighting anatomy as one strong link between art and science), or intense visual examination—as a zoologist might scrutinize the physiology and behavior of a furry creature. By way of illustration, Stein’s employment of taxidermy to construct photographic reenactments of the interaction of man and animals in a small, rural, Pennsylvania town, serves as what she describes as “modern dioramas of our new natural history.”

To quote artist, Justine Cooper: “Beyond the science, the historical and contemporary motivations for collecting, preserving, cataloging, and systematizing the natural world ultimately say more about Homo sapiens than any of the species represented in these vast holdings (of the Museum of Natural History in New York City).”

![Click for sizes / editions / prices. Elliot Ross, Animal [127], White Rabbit](https://clampart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Ross_Animal-127-bunny1-640x480.jpg)

![Click for sizes / editions / prices. Elliot Ross, Animal [127], White Rabbit](https://clampart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Ross_Animal-127-bunny1-415x550.jpg)