September 10 – October 24, 2020

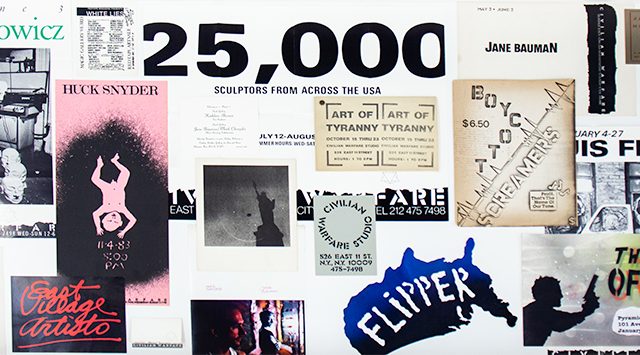

“Empty Stencils: The Street Art of Jane Bauman, David Wojnarowicz, and Artists From Civilian Warfare Gallery”

Curated by Greg Ellis

Opening reception:

Thursday, September 10, 2020

2:00 – 7:00 p.m.

ClampArt and Ward 5B are proud to present “Empty Stencils: The Street Art of Jane Bauman, David Wojnarowicz, and Artists From Civilian Warfare Gallery.”

In the late 1970s and 1980s, stencils were popular in punk culture and utilized to create gig fliers, album covers, and homemade T-shirts and clothing. Stencils eventually made their way onto the sidewalks in the form of street paintings. The ease with which images can be replicated using stencils makes them attractive to many artists. With stencils one can occupy tight spaces and paint unconventional surfaces while creating images rapidly. Stencils also lend themselves to collaborative projects of social, political, and activist intent. Such was the case with the work of Jane Bauman, David Wojnarowicz, and other artists represented by Civilian Warfare Gallery.

Jane Bauman’s history with stencils began while she was attending San Francisco Art Institute and getting involved in the Bay Area punk community in the late 1970s. The use of stencils became a method of communication among peers. The first seeds of collective artistic activism were sown for Bauman in the nightclubs, gay bars, and mosh pits of the punk landscape and included work with artist Mark C. Her participation in this rebellious youth movement and its do-it-yourself philosophy would increase in scope when she relocated a few years later to New York City, where No Wave and artist collectives were creating alternative culture. Bauman’s use of stencils as a medium to propagate images and messages on the city streets eventually influenced her Civilian Warfare co-conspirators. This was the group of young artists assembled by gallerists Alan Barrows and Dean Savard.

In 1982, Barrows and Savard established Civilian Warfare, which was among the new outlier galleries in the East Village of Manhattan, far away from the staid art world of SoHo and uptown, from which they were excluded. Barrows provided practical business acumen and Savard had a knack for spotting new talent; together the two men launched the careers of many of the era’s most important artists.

In 1980, two years prior to the establishment of the gallery, Bauman befriended artists David Wojnarowicz, Huck Snyder, and Luis Frangella, and they began stenciling together, in pairs or groups, on the Hudson piers and the Lower East Side. The camaraderie that existed between the artists—often with one acting as lookout, watching for neighborhood muggers and over-zealous cops—was generally experienced in the dead of the night with danger lurking around every corner. Within the neighborhood, these stencil paintings created a forum of anonymous messaging, often using archetypes drawn from the urban squalor. Amidst an economic recession, relentless violence, crack and heroin epidemics, along with a devastating new microbiological disaster, street art provided an outlet for the frustrations of a growing community of artists and radicals.

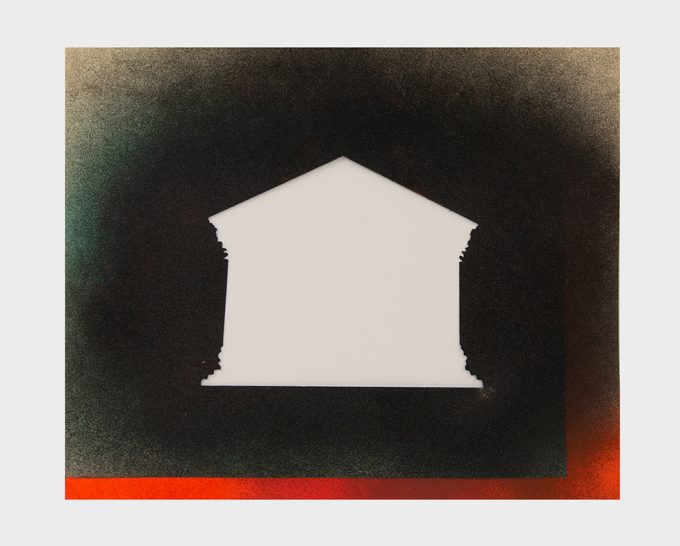

Bauman and Wojnarowicz eventually created the “Men in Distress” series, which included her “Seated Man” and his “Falling Man” iconography. It was Bauman who initially utilized the imagery of an empty house, which Wojanrowicz would famously set aflame to create his iconic “Burning House” stencil. The use of subjects related to emotional fatigue, disintegrating structures, and existential disfigurement were in no small part reactions to the AIDS crisis that was claiming the lives of those in the Lower

East Side queer and IV drug user communities, which would soon begin to take these artists’ lives as well.

Aside from the youthful deaths of this group of artists, their collective erasure was reflected in the disappearing stencil paintings they had left behind on the city streets. David Wojnarowicz writes of this sense of becoming invisible in his last essay, “Spiral,” as he describes his own death: “Sometimes I come to hate people because they can’t see where I am. I’ve gone empty, completely empty and all they see is the visual form: my arms and legs, my face, my height and posture, the sounds that come from my throat. But I’m fucking empty.”

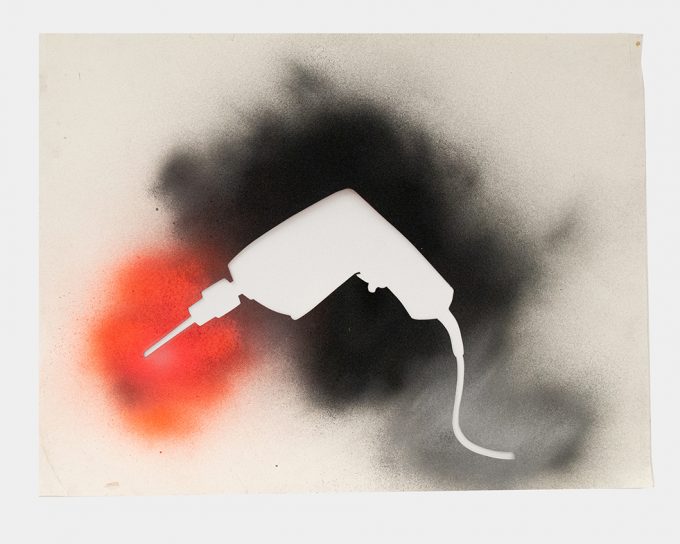

The stencils included in the exhibition not only represent documents of visual images erased by the elements over time, but are also poignant reminders of the many losses the East Village art community suffered during the early years of the AIDS pandemic. The missing positive imagery of stencil work is memorialized here in the negative templates left behind. Of that era, Bauman writes: “We were all so young—it seemed so cruel. Coming to terms with such losses, if we really ever can, is the work of a lifetime. And I never want to forget. To me, the empty stencils are such a poignant depiction of the loss, especially the dangling phone: all those calls about another AIDS diagnosis, another hospital visit, another death.”

Ward 5B is an archival and curatorial service specializing in late 20th-century urban ephemera and art, with a focus on punk aesthetic, radical spaces, performance art, drag, experimental theatre, camp, queercore, and guerrilla/street art projects.

A fully-illustrated catalogue designed by Erin Sheehy will be available for purchase.